FR | EN

The animal in the tuareg children's play and toys

Jean-Pierre Rossie

Nordic Center for Research on Toys, and Educational Media, Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

Nordic Center for Research on Toys, and Educational Media, Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

Introduction

A fundamental aspect of all cultures and societies is made up by ludic activities such as entertainment, play and toys. Yet, this cultural heritage and especially the children's games and toys are often neglected at least by the adults. Nevertheless, each child experiences their importance in his or her personal development and integration into the society.

This article, reprinted with some minor changes from the revue Tifawt (Meknès, 1996, n° 8), not only wants to describe but also hopes to stimulate the acknowledgment, the study and the use of this vanishing heritage, all this as well with respect for tradition as for change. It certainly would be very interesting to learn more about the attitude of the Amazigh (Berber) communities towards children's play, games and toys, possibly also through an analysis of the proverbs and sayings related to them.

A fundamental aspect of all cultures and societies is made up by ludic activities such as entertainment, play and toys. Yet, this cultural heritage and especially the children's games and toys are often neglected at least by the adults. Nevertheless, each child experiences their importance in his or her personal development and integration into the society.

This article, reprinted with some minor changes from the revue Tifawt (Meknès, 1996, n° 8), not only wants to describe but also hopes to stimulate the acknowledgment, the study and the use of this vanishing heritage, all this as well with respect for tradition as for change. It certainly would be very interesting to learn more about the attitude of the Amazigh (Berber) communities towards children's play, games and toys, possibly also through an analysis of the proverbs and sayings related to them.

But let us have a look at the way in which Tuareg children have integrated the animal world into their games, an animal world so familiar to them. However, it is first of all necessary to say something about the Tuareg themselves. Recently the number of Tuareg has been estimated at 1,3 million: 750,000 in Niger, 400,000 in Mali, 60,000 in Algeria, Libya and Burkina Faso. These Tuareg live in an enormous territory extending over the Sahara and the Sahel. The height of these territories varies between 500 and 2,000 meters. Until the 1930s the Tuareg lived a nomadic life and were excellent dromedary breeders but since the 1950s their traditional way of life vanishes more and more.

The play activities and the toys described here belong to this more or less traditional way of life. However, this does not mean that they have totally disappeared. Moreover, some traditions survive the changes imposed by the modern world through the games and toys of the children.

The dromedary in the tuareg children's play and toys

The dromedary, this animal so well adapted to the desert, naturally has stroke the imagination of the Saharan children and so it is quite usual that the dromedary is found in a lot of the Tuareg children's games and toys. Yet, before making toy dromedaries these children already play with little dromedaries.

The play activities and the toys described here belong to this more or less traditional way of life. However, this does not mean that they have totally disappeared. Moreover, some traditions survive the changes imposed by the modern world through the games and toys of the children.

The dromedary in the tuareg children's play and toys

The dromedary, this animal so well adapted to the desert, naturally has stroke the imagination of the Saharan children and so it is quite usual that the dromedary is found in a lot of the Tuareg children's games and toys. Yet, before making toy dromedaries these children already play with little dromedaries.

Among the Tuareg the little herds boys and herds girls make toys figuring dromedaries. They are possibly cut out of a flat tone, made with a jawbone of a goat or a sheep, with vegetal material (little branches, leaves), with rags. As shown at figure 1 and 2, the carved stones look more or less alike but the Tuareg children give them specific meanings according to their shape. For them, it is a male dromedary, the stone with a notch in its base (fig. 1), or a pregnant dromedary, the stone with a large flat base (fig. 2). A little dromedary is represented by a small stone. Next to these very schematic dromedaries there are others having a more elaborated shape as can be seen at figure 3. This toy dromedary was carved by a Tuareg Kel Ajjer child from the Algerian Sahara in the 1950s.

The Tuareg girls and boys put their stone dromedaries in the sand on a line or in a circle. They also use the vocabulary used in the breeding of these animals. The name given to these toys is "tifersîtin", singular "tafersît" (Archier, 1953: 39; de Foucauld ,1951-1952: 358).

The Tuareg children also create a series of toy dromedaries with a goat's or a sheep's jawbone. Figure 4 shows that this can give a masterpiece like the one made in the 1930s by a twelve-year-old boy from the Tuareg Kel Ahaggar of Idèles (Algerian Sahara). It is a saddled dromedary, of 27 cm height, mounted by a dromedarist or warrior of 16 cm height. Among the Tuareg of this region and those from Ghât in Libya these toys are called "aknar". For the Tuareg Kel Ajjer of Djanet in Algeria, the name "amajor" has been mentioned.

The Tuareg children also create a series of toy dromedaries with a goat's or a sheep's jawbone. Figure 4 shows that this can give a masterpiece like the one made in the 1930s by a twelve-year-old boy from the Tuareg Kel Ahaggar of Idèles (Algerian Sahara). It is a saddled dromedary, of 27 cm height, mounted by a dromedarist or warrior of 16 cm height. Among the Tuareg of this region and those from Ghât in Libya these toys are called "aknar". For the Tuareg Kel Ajjer of Djanet in Algeria, the name "amajor" has been mentioned.

Another model of toy dromedaries made by Tuareg children has a structure consisting of a dromedary dropping into which acacia thorns are stuck. A double thorn figures the head and neck, one thorn being used for the legs and the tail (Bellin, 1963: 99). Edmond Bernus shows a nice photograph of a young child of the Tuareg Kel Dinnik (Sahara of Mali) with a dromedary made with dromedary droppings and tiboraq thorns (1975: 174).

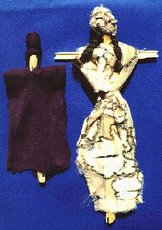

Figure 5 shows the kind of toy dromedaries made with vegetal material and cotton or woolen rags. This dromedary, collected in 1974 at Talat in the Aïr (Sahara of Niger), has little branches as legs stuck into a cushion filled with rags and serving as trunk. The head and the neck of the animal as well as the dromedarist doll are made with twisted palm fibers. This dromedary has been dressed in a white cloth. Its black hairdos is embellished with red and green tassels of wool attached with a safety pin.

Figure 5 shows the kind of toy dromedaries made with vegetal material and cotton or woolen rags. This dromedary, collected in 1974 at Talat in the Aïr (Sahara of Niger), has little branches as legs stuck into a cushion filled with rags and serving as trunk. The head and the neck of the animal as well as the dromedarist doll are made with twisted palm fibers. This dromedary has been dressed in a white cloth. Its black hairdos is embellished with red and green tassels of wool attached with a safety pin.

The last type of toy dromedaries described here is modeled with clay and then dried in the sun. The mounted dromedary of figure 6 (total height 14 cm) was created by a Tuareg Kel Ajjer child from the Algerian Sahara and collected in Djanet in 1934-1935.

An article published by an anonymous author under the title "Vie des Touaregs. Enfance et Jeux", written after 1945 but before 1960, offers some very useful information concerning the Tuareg Kel Ahaggar and Kel Ajjer children of the Algerian Sahara. According to this author the structure of the toy dromedary is made by the boys with pliable acacia branches. This structure is then dressed with rags by the little girls who finally cover it with a nice piece of white textile to give it the appearance of a chiefs mount. Sometimes, when the sewing of this small masterpiece becomes too difficult for the little inexperienced fingers, the help of a woman of the family is sought after. A woman who does not consider it beneath her to give help in making such a toy. Every detail of the animal is scrupulously represented: the head is well designed with little pieces of wood, carved and carved again by the artist of the children's group: eyes, ears, mouth, nothing is missing. The form of the hump is often well executed. However, seen in profile, the dromedary only has two legs that are stuck into the sand to keep it upright. It is another boy who carves the saddle from a piece of softwood, preferably tamaris, so that it totally resembles the 'rahla tamzak', decorated by burning the wood with red-hot needles. Then the saddle has to be attached to the animal by means of a little girth and its pompom, just as with the normal harness. Later on, the whole group starts to cut out of pieces of skin: the bridle, the dabias, the areg, the whip and the saddle carpet.

These dromedaries are mounted by a nicely dressed dromedarist doll with a similar structure. They form the central figures of the play activities next to whom the rest of the family is put in place: the mother, with her large dresses and whose feet of wood are strangely fixed into a clay ball so that when put on the ground and pushed the doll swings what should represent the walking, the children of every size and also the black servants. To these figures are added the animals and objects commonly found in a camp: pack dromedaries, goats, dogs, mules, carpets, cooking pots, water skins and also the tent cut out of a piece of skin. Once all the figures and objects have been made, the children play at 'tribal life'. While the boys, with the head of the family sitting on his white dromedary and the pack dromedaries loaded with sand sacks, follow the trails designed in the sand, turn around the hills of little stones and water their convoy at imaginary wells, this way covering thousands of kilometers on a strange relief map where the proportions are far from being respected, the little girls, who remained at the camp, mount the tent, send the rag black servants to herd the clay goats, simulate a tasty and time consuming cooking and finally realize an excellent dinner with three dates. When the boys, after a long journey of hundred meters, come back to the camp, the whole group of children plays at the joyful festivities that welcome the caravans coming back from Sudan (Folklore touareg. Fêtes et ludisme: 93-94).

These dromedaries are mounted by a nicely dressed dromedarist doll with a similar structure. They form the central figures of the play activities next to whom the rest of the family is put in place: the mother, with her large dresses and whose feet of wood are strangely fixed into a clay ball so that when put on the ground and pushed the doll swings what should represent the walking, the children of every size and also the black servants. To these figures are added the animals and objects commonly found in a camp: pack dromedaries, goats, dogs, mules, carpets, cooking pots, water skins and also the tent cut out of a piece of skin. Once all the figures and objects have been made, the children play at 'tribal life'. While the boys, with the head of the family sitting on his white dromedary and the pack dromedaries loaded with sand sacks, follow the trails designed in the sand, turn around the hills of little stones and water their convoy at imaginary wells, this way covering thousands of kilometers on a strange relief map where the proportions are far from being respected, the little girls, who remained at the camp, mount the tent, send the rag black servants to herd the clay goats, simulate a tasty and time consuming cooking and finally realize an excellent dinner with three dates. When the boys, after a long journey of hundred meters, come back to the camp, the whole group of children plays at the joyful festivities that welcome the caravans coming back from Sudan (Folklore touareg. Fêtes et ludisme: 93-94).

Notes

The toys shown in this article belong to the collection of Saharan and North African toys of the Département d'Afrique Blanche et du Proche Orient of the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. The photographs were made by the photographers of the Laboratoire de Photographie of this Museum. Reproduction of these photographs is not allowed without an authorization.

List of figures

Bibliography

The toys shown in this article belong to the collection of Saharan and North African toys of the Département d'Afrique Blanche et du Proche Orient of the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. The photographs were made by the photographers of the Laboratoire de Photographie of this Museum. Reproduction of these photographs is not allowed without an authorization.

List of figures

- Dromedary of carved stone, Tuareg Kel Aïr, Collection of the Musée de l'Homme, n° 71.39.5.3, 1971, photo Laboratoire de Photographie du Musée de l'Homme.

- Dromedary of carved stone, Tuareg Kel Aïr, Collection of the Musée de l'Homme, n° 71.39.5.27, 1971, photo Laboratoire de Photographie du Musée de l'Homme.

- Dromedary of carved stone, Tuareg Kel Ajjer, Collection of the Musée de l'Homme, n° 62.128.4, 1959, photo Laboratoire de Photographie du Musée de l'Homme.

- Toy-dromedary and dromedarist doll, Tuareg, Collection of the Musée de l'Homme, n° 41.19.113, 1938, photo D. Ponsard.

- Dromedary with dromedarist, Tuareg, Collection of the Musée de l'Homme, n° 74.107.6, 1960, photo M. Delaplanche.

- Dromedary and dromedarist, Tuareg, Collection of the Musée de l'Homme, n° 37.21.104.1/2, 1934-1935, photo M. Delaplanche.

Bibliography

- ARCHIER L. (capitaine), 1953, "Note sur les chameaux-jouets", in Bulletin de Liaison Saharienne, Alger, tome IV, n° 15, p. 38-39 .

- BELLIN P., 1963, "L'enfant saharien à travers ses jeux", in Journal de la Société des Africanistes, Paris, tome XXXIII, fasc. 1, p. 47-103.

- BERNUS Edmond, 1975, "Jeu et élevage. Vocabulaire d'élevage utilisé dans un jeu de quadrillage par les Touareg (Iullemmeden Kel Dinnik)", in Journal d'Agriculture Tropicale et de Botanique Appliquée, Paris, Tome XXII, n° 4-5-6, avril-mai-juin, p. 167-176, ill.

- de FOUCAULD Charles (père), 1951-1952, Dictionnaire touareg-français. Dialecte de l'Ahaggar, Imprimerie Nationale, Paris, 4 vol., 2028 p., ill.

- "FOLKLORE TOUAREG. FÊTES ET LUDISME", anonyme, in Études et Documents Berbères, n° 1, La Boîte à Documents, Paris, p. 86-99, ill.

- "VIE DES TOUAREGS. ENFANCE ET JEUX", anonyme, 1987, in Études et Documents Berbères, n° 2, La Boîte à Documents, Edisud, Aix-en-Provence, p. 91-98.